#TLT17 Part 2 Challenge, Differentiation and Inclusion- Planning (the before).

This is part 2 of 3 of my #TLT17 session. In part 1 I acknowledged this blog by @teacherhead, this blog by @atharby and this blog by @chrishildrew. I must confess that I hadn’t realised just how much Chris’s blog had influenced much of my thinking, particularly over the use of the term ability.

Part 1 was more about the philosophy behind inclusion, challenge and differentiation. This blog is more on how we can plan lessons which are challenging but inclusive.

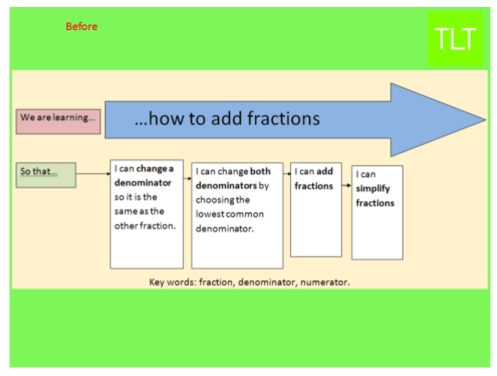

In terms of ensuring challenge, I use SOLO taxonomy to set my expected learning outcomes. They look something like this:

I know that SOLO has its critics but for me it’s a key way that I ensure that what I am asking my students to do is sufficiently challenging. This blog by @Andyphilipday advocates SOLO but spells out the dangers of its misuse (particularly in thinking it is a race to extended abstract). For me, SOLO works because it means that making links between well understood (and remembered) scientific facts, ideas or concepts is at the heart of what I ask my pupils to do. And this means that I set challenging tasks.

The key to my use of learning outcomes for pupils (the so that part) is that my expectation is that all pupils will be able to achieve all of them. There is no some, most, all. I may need to provide additional support to some pupils but my expectation is that all will strive to get/do/achieve/whateveryouwanttocallit each learning outcome.

Lesson planning should always start with what do I want pupils to learn (rather than what activity they are going to do). Once that is established, you design tasks that enable pupils to work with this content. SOLO really helps me design challenging tasks.

Whether you use SOLO or not (and I really do recommend using it, particularly in content heavy subjects) the most important question to ask when planning your lesson is:

Of course it may be for a sequence of lessons but you get the drift. This means looking at the content that you are teaching as well as the work that you are going to ask pupils to complete.

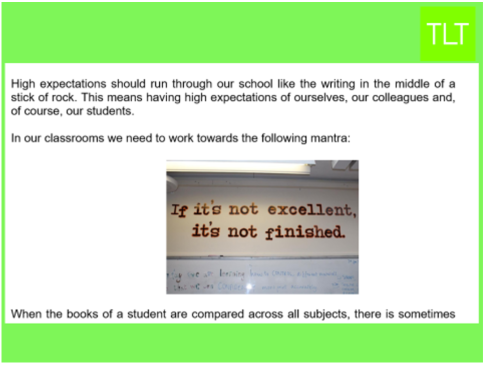

This photo is from @ChrisMoyse and it features in our school’s 10 features of effective lessons. The image is springing up in many of our classrooms.

But the question is, does your task design allow students to show excellence? In addition, knowing your students is vital. Our students will have different starting points so what represents excellence for one pupil might not represent excellence from another pupil. The key here is knowing your students well enough to know what excellence looks like from them AND THEN having an expectation that what represents excellence will change as the bar is raised for each and every student over time.

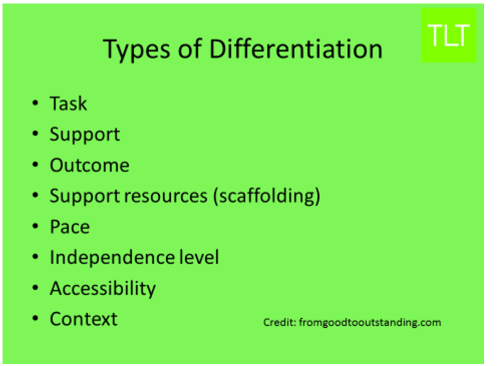

In terms of how we can successfully differentiate, a google search typically gives something like this:

This list is by no means exhaustive and it can quickly become quite overwhelming if you consider every possible way that differentiation could be achieved.

For manageable differentiation (big nod to @atharby here), think about differentiation before and during. The before is when you plan the lesson (covered in this blog), and the during is obviously as the lesson unfolds.

Type a is linked with your teaching (particularly your explanations) and type b is linked with the pupils and their undertaking of the task(s) you have set them. Type a is to do with the misunderstandings and misconceptions that pupils can have with the content. Type b is to do with pupils’ difficulty in completing the task (and what help/support/scaffolding may be needed).

Before -Type a- plug gaps before they appear.

This is where subject knowledge really comes into it. Over the last few years I have been a little sceptical when I have read about the importance of subject knowledge. I wondered whether having a better understanding of action potentials and potassium gates would help me teach KS4 Biology. But if subject knowledge is linked with what and how pupils think about my subject then I am fully on board. We have beautiful, finely crafted cathedrals of knowledge in our brains (our subject schema) and we try to build this schema in our pupils’ brains. The curse of the expert means we sometimes overlook what it is to be a novice with incomplete schema. We have to remember that very often we are building and linking new knowledge with shaky prior knowledge. Our pupils’ cathedrals of knowledge (their schema) are lacking the necessary foundations to build on. This is where subject expertise comes in. This is particularly true lower down the school. The better we can teach, with common misconceptions and misunderstandings at the forefront of our minds, the better the foundations of their subject schema will be. And quite possibly (well almost certainly), less differentiation will be needed further up the school. We have to plug gaps before they appear, and this means having a clear understanding of what these gaps may actually be.

A few years ago, when teaching a Year 9 maths class, we had a few lessons coming up on adding and subtracting fractions. Even with my limited subject knowledge I anticipated that working out the lowest common denominator would be the bottle neck of the learning. This would be the area that most would struggle with. This would be the area that the biggest gap could appear.

In an effort to plug this gap before it appeared, the lesson started with recap work, a starter task on lowest common multiple. In fact, through spacing, I had ensured that pupils were still comfortable with working out the lowest common multiple of 2 numbers. Once the starter had been done, and any mistakes reviewed and discussed, pupils did not struggle with choosing the lowest common denominator. That simple anticipation, made when planning the lesson, had meant that the lesson went far better than it might have. If I hadn’t done the starter then it is likely that some pupils would have struggled which could have left me thinking that I should have differentiated in the lesson.

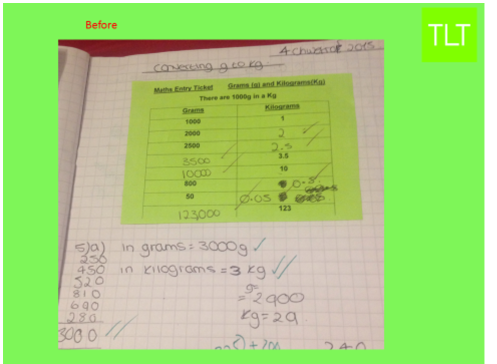

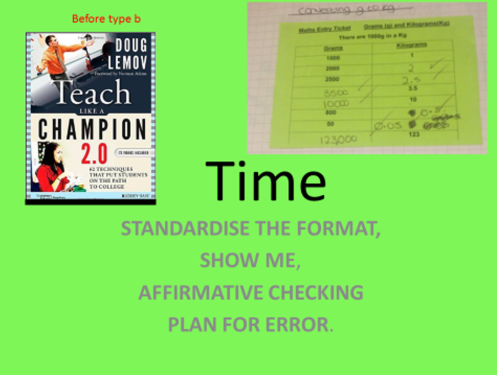

Staying with Maths, I was teaching a lesson where, if pupils were to be successful, they would need to be comfortable with mixed units of grams and kilograms. I anticipated that this may be the bottle neck of the lesson (or the biggest gap in their knowledge) so I gave the pupils an entry ticket which they did before they started the main task. This ensured that any difficulty in completing the task would not be because they couldn’t convert between units fluently.

I will return to entry tickets later on.

The above examples are just one way of plugging the gap. The usual and most straightforward way would be to plug the gaps during your explanation. The best example I can give is teaching KS3 students about respiration. It is an ongoing frustration that pupils continue to conflate breathing and respiration. When teaching KS3 pupils, I will make explicit the links between the 2 processes but also explain how they are different. I will even cover WHY people conflate them (the lungs being part of respiratory system, artificial respiration etc). I won’t leave it to chance that they will be clear on the differences between the 2 processes. I will also revisit this key concept in the coming months. This should ensure my pupils get to KS4 with a tacit understanding of what respiration is (and why it is NOT the same as breathing). Again, this will limit the need to differentiate later.

This is where dual coding comes in too (see part 1). If your explanations can plug gaps and are accompanied by complementary graphics that limit cognitive load, then the need to differentiate at a later date will be reduced.

So type a (of the before) is all about knowing the common misconceptions and misunderstandings your pupils may have. And we plug those gaps before they appear. Of course it is impossible to predict every misconception pupils may have (this is where formative assessment and classroom routines come into it) but we can plug the usual, common ones. And the more years that we teach, the more aware we should be about these common gaps. These common gaps should be discussed in subject meetings. And plugged in class. Before they appear.

Before – Type b- difficulty in completing the task.

Picture the lesson: you have delivered your explanation and plugged the main gaps before they appear. Now the pupils are going to undertake their task. The trick is to anticipate the difficulty that pupils may have with the task and how they can be supported.

Scaffolding is a great term as the support that you provide individual pupils can be reduced and removed as time goes by. I stole a great analogy from @BodilUK‘s blog on scaffolding. There are 2 types of support that novice bike riders can be offered. The top right is the traditional stabilisers option. The bottom right is learning on a balance bike. Bodil rightly argues that when children learn to ride bikes, the key is that they successfully learn how to balance. Stabilisers take away the need to learn how to balance. So whilst children can have the illusion that they are successfully riding their bike, the stabilisers have done all the hard work for them. Far better to use a balance bike. The pedalling has been removed but children have to learn and master the key attribute of balance.

Selecting the right scaffolding for our learners is analogous to this. It should help them access and complete the task but it must not do the thinking for them. The scaffolding must not do the cognitive work for the learner.

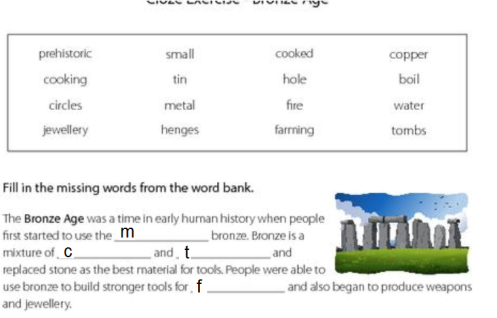

If you are doing a clozed exercise (pupils fill in the blanks) and you provide the missing words at the top of the worksheet then this will support pupils but won’t do all of the thinking for them (as long as some of the words could possibly go in multiple gaps). However, if the first letter is provided like this:

then it becomes nothing more than a matching exercise. The first gap is metal by default as it is the only m. Using a resource like this removes, or massively reduces the thinking pupils have to do. It must be avoided.

I am not a big fan of closed exercises but without the first letter this is far more legitimate task. Disclaimer- I used a google image search for the resource and added the first letter myself (on paint). This is not what the resource looked like. The above was just to illustrate the point.

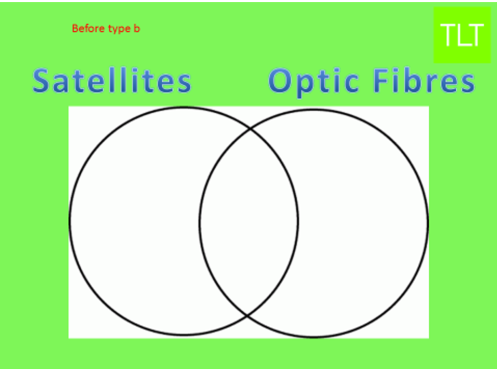

A few years ago I was teaching the similarities and differences between optic fibres and satellites (GCSE Physics). I gave pupils a venn diagram:

I would then reveal 10 sentences on the board and pupils would write each sentence in the relevant section of the venn diagram. In the first year that I did this, many pupils would finish in the “expected” time but some pupils (whether to do with speed of handwriting or processing issues) would not. In fact, many would have only completed 3 sentences by the time I was going through the answers. This meant that they only participated in a small part of the activity and the task design had limited their thinking.

The following year I simply used the same 10 sentences but with 1, 2, 3 etc before each sentence. Pupils then had to put the number in the correct area of the venn diagram. All pupils were finished within a few minutes. All pupils had thought about where each sentence should go. Again, it didn’t look like differentiation but without it I would have excluded some pupils from the task and left me with the feeling that I should have differentiated. This tweak is a good example of how, when planning our lessons, we need to critique every task we ask pupils to do, before we consider what scaffolding is required. I am not a fan of clozed exercises. When pupils are copying out closed exercises into their books it is a criminal waste of learning time (unless the purpose is handwriting practice). The only thinking involved is what goes into the gaps. The rest is just copying. What a waste of time. The change in approach with the venn diagram freed up precious learning time by removing pointless copying time.

Here are some more examples of scaffolding:

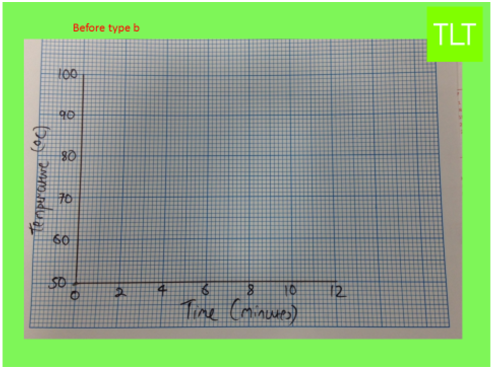

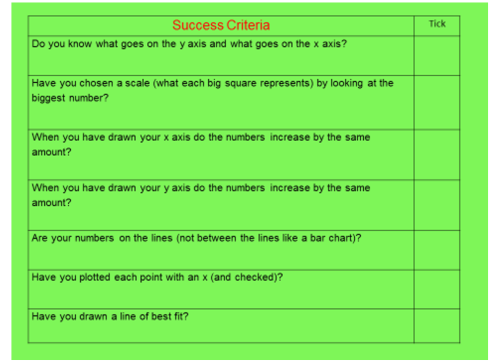

This could be used by some pupils as their actual graph. It could be used by others to help set out their graph. Some pupils may not need the scaffolding at all. These could be available face down on the table and pupils use the scaffolding if they need to. This still ensures that pupils plot a graph. This scaffolding can be changed to this (as time goes by as pupils gain in independence and graph drawing skills):

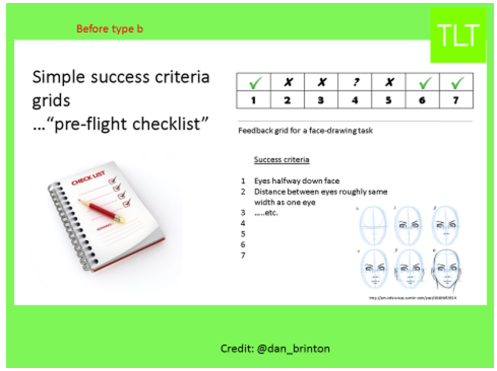

More examples of scaffolding are:

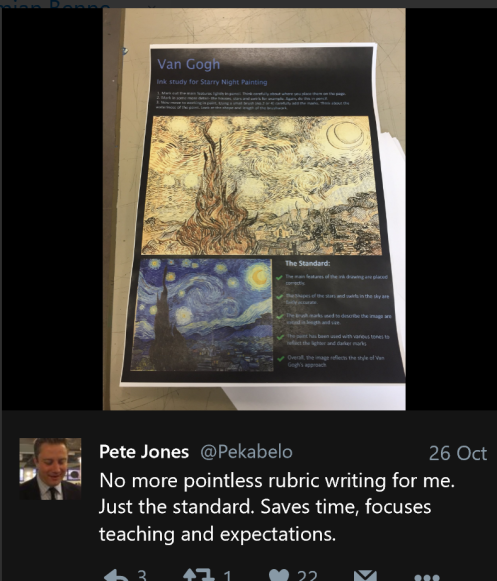

(Post session addition)- or this brilliant one from @Pekabelo where a rubric is replaced with a standard – the expectation is all pupils work to meet it:

Or this by @atharby:

If you are teaching a lesson on fair trade in geography you may want pupils to access this information (credit to Matt Grant and also @ASTsupportAAli):

You may anticipate that some in your mixed attainment class are going to struggle with the reading, particularly because of the vocabulary involved:

There are 3 choices available for you pre lesson.

- Give some pupils a reduced version with many of the key words removed. The massive downside to this is that these are the very pupils that need to be exposed to the key academic vocabulary. If you withhold the vocabulary as it is too demanding for them then they are going to fall even further behind their language rich peers. How can they close the gap with this approach?

- Plough on with the text and help students as they work through it. Better than point 1 but plenty of issues here. Or:

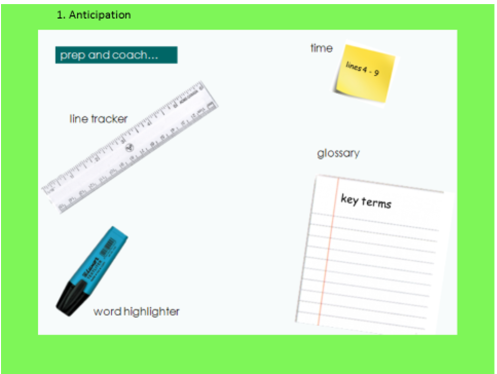

- Tweak the resource:

Go through a few lines at a time. “Coach” pupils to highlight key words that they are unsure of. Then define them as you move through the lines.

My wife made a valid point when I showed her this. She asked what if pupils are too embarrassed to highlight and communicate that they don’t know certain words. The answer to this is to ensure that you create a classroom culture where it is ok to make mistakes and for pupils to be comfortable to admit they don’t know certain things. As teachers we set the classroom climate and we must strive to have a classroom of high expectations hand in hand with pupils being comfortable being wrong as it is just a part of learning. I know this sounds cheesy (and is) but that is what we strive for.

Post blog edit. Huge thanks to @JulesDaulby for suggesting the use of immersive reading in word 365 online (see here). Pupils that have decoding issues could use this programme. There is also free text to speech in word 2016 (see here). These “read” the words and the reading speed can be varied. Electronic textbooks can be used this way and pupils with visual impairments or decoding issues can have them for free.

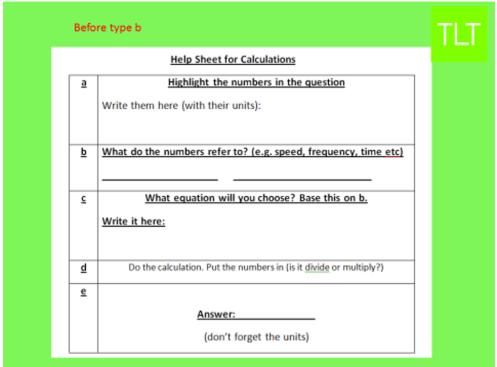

It may well be that for some tasks scaffolding won’t be appropriate and what some students may need is simply more time with the teacher. When I used to teach Maths I regularly used “entry tickets” (idea from @Doug_Lemov’s fantastic TLAC2).

Entry tickets are given to pupils and they need to complete them successfully before they attempt the main piece of work. Pupils bring them up to my desk and if they get them all right they start the main task. The entry ticket task as to be linked with a key element of the main task. More detail is provided here.

The way that I used these entry tickets would be to (as subtly as possible) hand them out to the higher attaining students first. By and large, these students would finish quickly, come out to my desk, get all answers correct and move onto the main task. This then means I am free to spend more time with the students that may be struggling with the task. I could reteach a small group or make further explanations an individual basis. Whatever I do, this entry ticket has bought me some time to spend with pupils that are struggling. Very often this is more appropriate than providing scaffolding. You could argue that the actual physical entry ticket is “gimmicky” but the principle can be applied in many different ways. And it can really help make your classroom an inclusive place.

This amount of thought required at the planning stage may seem overwhelming. But as a teacher gains experience then planning to account for type a and type b will become second nature. It will just become a part of planning lessons.

This is the end of part 2. Part 3 will look at what should happen during the lesson. This will focus on ensuring we have robust, embedded classroom routines that allow us to be truly responsive.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks